By Charles Petrie, Senior Advisor at ARDD

1.Context

Myanmar represents the paradox of a country blessed with an extraordinarily rich natural resource base, but where for decades conflict, mismanagement, national seclusion, and international isolation have led to deteriorating economic growth and increasing poverty. Myanmar is made up of an intricate mosaic of different ethnic, cultural, and geographic entities. It is a nation of great geographic and ethnological diversity with officially more than one hundred and thirty ethnic groupings having different languages, religions, customs, and histories. The topography of the country – mountain, hills, delta, and dry zone – further contributes to the diversity, with different groups having developed histories and forged identities that are not necessarily defined by administrative boundaries.

Myanmar has had a troubled history of almost continuous conflict since independence, for the most part pitting the ethnic minorities against the (Bamar) majority-dominated military. At the time of independence, the very notion of the Union was not accepted by many ethnic groups within the country. Decades of insurgencies reinforced the mutual suspicions between the majority ethnic group and the ethnic minority populations.

Everything changed on 1 February 2021, when the Commander in Chief, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, staged a coup, annulling the results of recently held elections. His actions triggered a fundamental transformation of Myanmar’s socio-political landscape. The Senior General seemed to have believed that the Tatmadaw (name of the Myanmar military) could follow the old playbook of violent oppression and military occupation that had worked in the late 1980s, early 1990s, and even 2007. But he hadn’t counted on the fact that Myanmar had become a fundamentally different country following its relative opening up to the international community in 2011. The young and civil society mobilized in a manner unseen before; administrative officials, public civil servants, and many workers took to the streets to protest.

And in so doing, a new political dynamic emerged, transcending the divides that had previously existed. For decades, the ethnic armed groups had been little interested in the Bamar majority’s fight for democracy, of which Aung San Suu Kyi was the leader, and the Bamar majority had paid little attention to the historic insurgencies that had been underway since independence along the border areas of the country. On 1 February 2021, the Senior General Min Aung Hlaing achieved what until then seemed almost impossible: uniting all the people of Myanmar … but against the military.

Myanmar is now in the midst of a significant transformation. The groups confronting the SAC are shifting their focus from consolidating their armed control over the areas they consider historically theirs to the establishment of new forms of local governance. Rather than breaking apart, Myanmar is being transformed into a mosaic of autonomously governed spaces, none of which are seeking independence. What is being asked for is a form of federalism that guarantees the rights of different ethnic groups and supports their ability to work together.

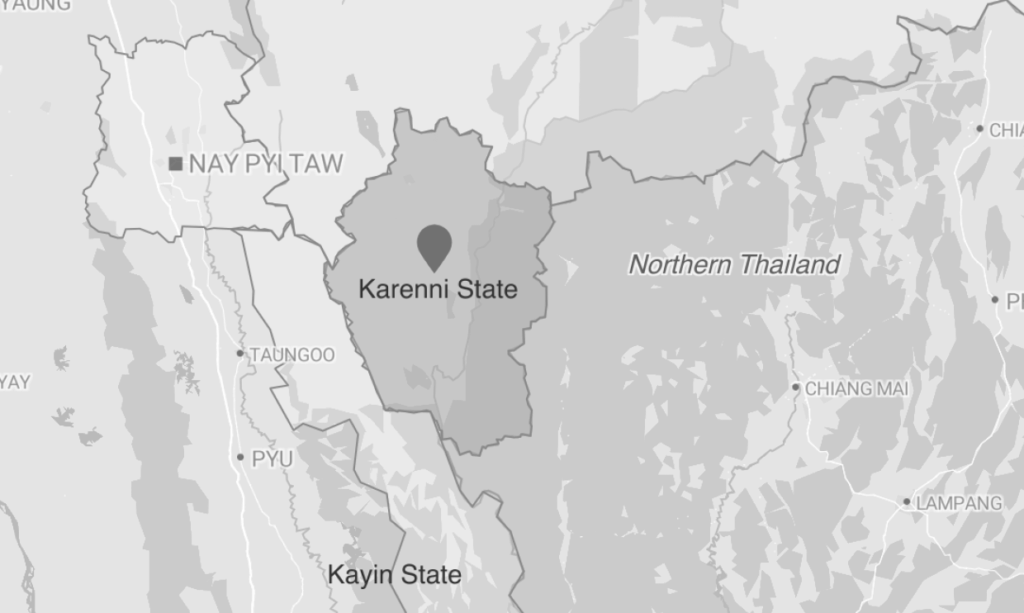

2. Karenni State

Karenni State, also known as Kayah State, is a small state in eastern Myanmar bordered by Thailand. It has a distinct history, having been given semi-independent status during British

colonial times. Before British rule, Karenni had been made up of several small, independent principalities ruled by local chiefs. These areas were inhabited predominantly by the Karenni people (a subgroup of the Karen ethnic group). When Burma gained independence in 1948, the Karenni states were merged into the Union as a Karenni State.

The Constitution of the Union of Burma in 1947 proclaimed that the three Karenni States be amalgamated into a single constituent state of the union, called Karenni State. It also provided for the possibility of secession from the Union after 10 years. In 1952, the former Shan state of Mong Pai was added, and the whole was renamed Kayah State. Under the 2008 constitution, Myanmar was formally divided into 21 administrative divisions, which include seven regions, seven states, one union territory, one self-administered division, and five self-administered zones. Karenni State was renamed Kayah State, with the state capital in Loikaw. The state is divided into 4 districts, which are divided into 7 townships with 106 wards and villages. Before the coup, executive authority was held by a State Government consisting of a Chief Minister, other ministers, and an Advocate General. The President appointed the Chief Minister from a list of qualified candidates in the regional or state legislature; in theory the regional or state legislature should approve the President’s choice unless they could prove that he or she did not meet the constitutional qualifications. Legislative authority resided with the State Hluttaw, made up of elected civilian members and representatives of the Armed Forces.

The estimated population in the 2014 Myanmar Census was 286,738, the smallest among Myanmar’s seven states. The Karenni make up the majority of Kayah State’s population, but significant minorities of Bamar, Shan, and Karen also inhabit the state. The Shan, Intha, and Bamar live in the north, and the Pa-O in the surrounding hills. Each group is also known by more than one name.

The reality is that, beyond formal administrative structures, in 1957, pro-independence groups formed the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP), backed by its own army, the Karenni Army (KA). Following a ceasefire in 1995, the fight for greater autonomy has been led for the most part by the political arm, the Karenni Nationalities Progressive Party.

The coup of 2021 triggered initial demonstrations against the military coup, which were peaceful. The protests were led by a young generation whose formative years had been the period of relative openness that Myanmar experienced in from 2011 to 2021. A generation who having tasted the relative freedoms of that decade was not ready to give these freedoms back. A generation interacting across all ethnic lines within the country and connected with the outside world. A generation that developed its music, traditions, values, and habits. But most importantly, a generation that had not inherited the fear of authority that had been so ingrained into their parents.

Initially the police, who were charged with confronting the protesters, hesitated, not knowing how to deal with so many people in the streets. They were quickly replaced by the military. It was in Loikaw, the capital of Karenni, that the military first opened fire and killed the first of the protesters. This ignited intense fighting in Kayah State. The combination of a new generation of activists and elements of local defence forces led to the creation of the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force (KNDF).

While being fully integrated with the Karenni Army, the KNDF is more of a revolutionary movement than a classic army. The KNDF is commanded and filled with young activists. The Deputy Commander of the KNDF, Commander Mawri, for example, is little over 31, and 3 before the coup, he was an organic farmer. The KNDF upper command believes that violence is to be used only when non-violent and peaceful ways have failed. But when using violence civilian populations need to be spared. The guiding philosophy of the KNDF is that when providing a gun to a young recruit, he needs to think about when he will give it back.

One year after its establishment, the KNDF issued its “Manifesto”. While situating the post-Coup conflict in the State’s broader historical struggle, the KNDF sees the current struggle as an all-or-nothing attempt to solve the underlying political problems that have plagued the country. The manifesto confirms the KNDF’s commitment to respecting human rights, its demand for equality for all ethnic nationalities, building consensus whenever possible, and seeking to foster co-existence and harmony between all the different groups. While seeking self-determination and autonomy within a federalist system, the KNDF does not rule out a return to its historic right of independence. Finally, in its manifesto, the KNDF renounces any role in politics and commits to subjugating the military to civilian authority once this is established.

4.Local Governance

Karenni is in the midst of an experiment in participatory democracy at all levels of the administration of the state. Those involved in this experiment believe that for the first time in Myanmar’s post-independence history, the people are involved in the decisions affecting their lives. While not underestimating the resistance from traditional political and community leadership, the Karenni leadership believes they can convince those resisting the change to join.

The experiment started almost immediately after the coup, when some of the key Karenni civil society leaders came together to agree on how to manage the period to come. Based on the principles of dignity, unity, commitment to the revolution, and an all-inclusive process, the Karenni State Consultative Council (KSCC) was formed. The KSCC was made up of civil society organizations, youth and women organizations, Karenni parliamentarians, and professionals from a variety of disciplines. Not all seats within the KSCC have been filled. A number have been left vacant to allow currently recalcitrant groups to join.

The agreement took some time to reach on the establishment of an executive structure, the Interim Executive Council (IEC), but it came into existence in June 2023. While assuming the responsibilities of a de facto state government, the IEC sees itself only as a caretaker entity established to set up the structures and systems of administration at the village, village tract, township, district and state levels. The IEC has a cabinet made up of seven members, of which only six have been named so far. Efforts have been made to ensure the cabinet is representative of the different forces active in Karenni; political, military, PDFs, and civil society (with a particular focus on women participation). Each constituency elected its representative to the cabinet. The seventh position left vacant for the participation of a still undecided political group. Theoretically twelve departments should be reporting to the IEC, though only eight have been established so far. These are Health, Education, Humanitarian, Projects and Finance, Women and Children, Judiciary, Home Affairs, and the Department of Trade and Commerce.

The IEC has a collaborative relationship with the KNDF. The Deputy Chair of the IEC is a KNDF senior officer. As the IEC grows in capability, it is planned that it will take on all the security responsibilities of the state. To date, only the responsibility of running prisons and policing has been transferred to it.

Karenni leaders have proposed the establishment of a jointly managed regional multi-donor trust fund, Karenni State Development Fund (KSDF). The primary objective of the pooled fund is to provide comprehensive support for humanitarian activities and to strengthen civilian resilience in Karenni State. Humanitarian activities will focus on providing emergency assistance to meet the basic needs of affected populations, including access to food, clean water, healthcare, education, and nutritional support. The design of the Fund aims to significantly enhance local ownership and accountability by ensuring that Karenni civil society, with the IEC being given a direct role in defining and directing investments. So far two donors have agreed to participate in the fund, while others have expressed interest in the establishment of this type of regional multi-donor trust fund.

4.Conclusion

The international community needs to understand how much the socio-political landscape in Myanmar has changed since the coup, and it needs to be willing to engage with the new realities. Chief among the new realities is understanding that the State of Myanmar can never effectively be a centrally governed one, at least in the short and medium term. Any attempt to impose such a model in the current context will only lead to much more violence and destruction. Instead, a new form of governance based on federalism, a federalism created from below and offering very broad autonomy to the federal units, needs to be promoted.

Of course, the fear exists within the international donor community that acknowledging and working with the emerging governance structures will contribute to further breaking apart the country. But it is important to remember that the current fragmentation is not only a result of the loss of control of the Myanmar military of many parts of the country, but also the emergence of alternative forms of local governance in the spaces created. None of the resistance or the ethnic groups is seeking independence. What is being asked for is a form of federalism that guarantees the rights of different ethnic groups and supports their ability to work together.

Engaging with local governance structures will necessitate being willing to accommodate new ways of working. Implementing approaches that support open-ended processes rather than well-defined outcomes, which in turn necessitates multi-year commitments rather than short-term funding cycles. In contexts where health, education, humanitarian, livelihoods, and wider needs and services are all equally urgent, it remains important to think (and program) cross-sectorally. More structural forms of intervention will need to be considered, such as supporting credit schemes and using non-traditional financial networks to facilitate cash transfers.

The international community needs to listen to what is happening in Myanmar. The population of Myanmar has suffered too much since its independence. The current “revolution” must lead to an end to the struggle for equality between all ethnic groups.