By Matilde Picarazzi, RSC Intern

Since October 7th, 2023, more than 270 journalists and media workers have been killed by Israeli forces in an apparent effort to conceal from the world the horrific realities unfolding in the occupied Palestinian territories. The deliberate military targeting of journalists and their profession leaves no doubt that these criminal acts are not mere incidents or collateral damage aimed at gaining military advantage, but a deliberate attempt to silence anyone who stands up for Palestinian rights. However, despite the clear breach of international and humanitarian law and the careful collection of evidence to ensure these crimes are not forgotten, there have still been no repercussions for those responsible for these war crimes.

Journalists, like civilians, medical personnel, humanitarian workers, and religious figures, are classified as non-combatants under international humanitarian law. As such, they may neither be lawfully attacked nor take part in hostilities. They are not legitimate military objectives and are entitled to special protection. The protected status of journalists is also rooted in the constitutional principle, common to many states, that guarantees the public’s right to information, even during times of war, as an essential component of democracy. Their protection is therefore crucial.

Media attention has long proven a powerful tool for raising public awareness and gaining international support. History offers many examples of journalists profoundly shaping how wars are seen and understood. One such case is the “Highway of Death,” which occurred during the night of February 26-27, 1991, when retreating Iraqi forces were attacked on the road from Kuwait to Basra. The widely broadcast CNN images revealed scenes of utter devastation, burnt vehicles, ashes, and the consequences of modern warfare, which deeply shocked global public opinion. Another powerful example came on August 5, 1992, when The Guardian journalist Ed Vulliamy, accompanied by a British television crew, reached the barbed-wire fences of the Omarska detention camp in Bosnia and filmed the prisoners inside. The footage, which provided undeniable evidence of the systematic “ethnic cleansing” carried out by Serbian forces, was broadcast worldwide and triggered widespread outrage across the international community.

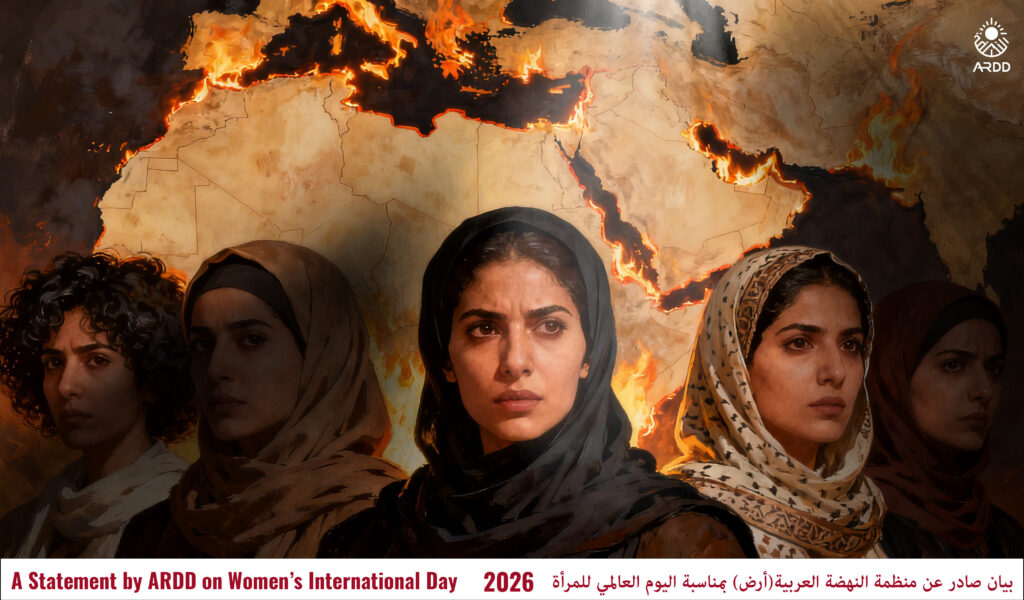

Over time, the media’s role in wartime has become increasingly vital. Public opinion and international responses are profoundly shaped by journalists who risk their lives documenting and reporting from conflict zones. In Gaza, journalists have been the voice and the eyes of a population under siege. They serve as witnesses, their reports offering hope that the truth will not remain hidden and providing visibility to those enduring the conflicts. The documentation of alleged war crimes in Gaza has fueled international criticism, as the exposure Palestinian journalists bring to the world threatens Israel’s global image and, under mounting public pressure, risks shacking the support from Western countries. Their work has allowed the world to witness the reality of the genocide firsthand, triggering a significant shift in international public awareness and solidarity in recent years. That’s why, perceived as a threat by Israeli forces, there has been a clear incentive to detain, silence, or remove media personnel to restrict information flow, isolate Palestinians in Gaza, and weaken their outreach capacity.

Nevertheless, under international humanitarian law, journalists are civilians, and deliberately targeting them is unlawful and may constitute a serious international crime. Evidence indicates that these attacks are not isolated incidents but part of a systematic, state-led policy. Journalists have been targeted by name, and their families have also become victims of reprisals. One tragic example is that of Shireen Abu Akleh, a Palestinian reporter who was killed by Israeli forces in 2022 while covering their invasion of Jenin in the West Bank. The shooting was intentional and directed at the press team, even though no Palestinian armed resistance was present at the place. Despite being clearly identified by the “PRESS” marking on their vests, helmets, and equipment, reports show that journalists in Gaza and in the region have been killed near hospitals, in public spaces, residential areas, and even in schools and shelters. These killings amount to a form of collective punishment, aimed not only at silencing witnesses but also at deterring the population from collaborating out of fear. Journalist Anas al-Sharif was among those killed after an airstrike hit his press tent near al-Shifa Hospital, a location that, by its very nature, should have been protected and excluded from any military targeting. The fear that their presence might draw attacks has left journalists increasingly isolated, cutting them off from the very communities they aim to represent.

This has led the ICC Prosecutor to include these crimes in the ongoing investigation into the Situation in the State of Palestine. However, the obligation to prosecute individuals suspected of committing or ordering war crimes against journalists is shared by all parties to the Geneva Conventions, not by Israel alone. Acting promptly is a collective responsibility, essential both to prevent the silencing of Palestinian voices and to ensure that history is not written solely by those who suppress Palestinian rights. Those committing crimes against journalists in Gaza bear individual criminal responsibility, but the chain of command is equally accountable as it has failed to act to prevent or punish such violations.

The urgency of enforcing these responsibilities has grown in the modern era. When the Geneva Conventions were drafted, the norms protecting media workers primarily referred to printed or broadcast content, newspapers, film, and television. Today, with the rise of instant communication technologies, anyone can share information globally. While this facilitates the rapid spread of news, it also makes everyone a potential target, which makes the prosecution of such crimes more critical than ever. In Gaza, popularity on social media can now be a death sentence, as it was for Palestinian journalist Saleh Aljafarawi. Still, the attacks on journalists do not stop at physical threats. The shadow banning and erasure of material from social media represent a new, digital form of silencing, one that “kills them twice.”

And Gaza is not an isolated case. Across other conflict zones, the same mechanisms of repression and censorship are unfolding. In Sudan, the collapse of state institutions and the absence of protective mechanisms have forced more than 400 Sudanese journalists to flee the country, paving the way for the devastating spread of war propaganda, misinformation, and hate speech, and leaving the population without access to life-saving information. In a climate of isolation, where raising one’s voice means facing criminal charges, journalism has become unsafe in both Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF)-controlled areas. The marginalization of Sudanese journalists is further compounded by the near impossibility for foreign correspondents to enter and contribute. Following recent events, with the RSF’s seizure of full control over Il Fashir, information has been further stifled, as demonstrated by the detention of Sudanese journalist Muammar Ibrahim by RSF forces.

From Palestine to Sudan, a subtle war is being fought not only with weapons, but through control of information and manipulating public opinion. As the keepers of history for future generations, we have a duty to preserve the truth of events, and that begins with protecting journalists who make truth visible. Defending them is not only an act of solidarity, it is an act of resistance against oblivion, essential to preserving accountability.