By Ella Hindermann, RSC Intern

Every year on the 20th of February, the global community marks World Day of Social Justice – reaffirming its commitment to justice, equity, democracy, and inclusive development. Yet for millions of people living in regions shaped by prolonged political crisis, these principles remain largely an aspiration and can feel unattainable. Although global commitments constantly stress social development and social justice as a necessity for the achievement and maintenance of peace and security, political realities on the ground often look very different.

Established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2007, the day was created to highlight the need to build a more equitable world for all and to urge efforts to combat unemployment and poverty worldwide. At the same time, it encourages social inclusion, an equitable distribution of income and greater access to resources through equity, equality, and opportunity at national, regional, and international levels.

The urgent need for social justice is not an abstract or sudden concern. Global social injustices are neither random nor new—they have developed over time and are structurally anchored. That is why global dynamics must be carefully considered when it comes to the international dimension of social justice, as they are connected to our post-colonial world order. Global disparities in access to resources, political power, and economic opportunities are not simply the result of contemporary policy failures. They are deeply embedded in historical processes that continue to shape the current international system. In many contexts, dynamics of inequality and exclusion can be traced back to colonial and post-colonial power structures, the process of creating modern states, and with that, a new world order that established economic interdependence and political marginalization until the present. For that reason, it is not surprising that unfair distribution of resources and access to opportunities between regions and nations leads to unequal development paths.

These historical power asymmetries continue to shape the global economic system today. While ongoing globalization and increasing economic interdependence have created new opportunities for economic growth and rising living standards in many parts of the world, they have also reinforced existing inequalities. In many contexts, economic interdependence has contributed to growing income inequalities, continuous unemployment, and increased poverty. This is especially the case in regions already affected by political instability and limited economic agency. With the constant presence of prolonged political crisis in regions like the Arab World, these global dynamics intersect with local governance challenges that further complicate the way to social justice and to inclusive and participatory societies.

An example where the challenge of achieving social justice in contexts of political instability becomes particularly visible is Syria. As a state including a great variety of ethnicities and religious belief systems, Syria has a long history of negotiating social and national identity, closely connected to fundamental questions of plurality, political participation, and representation. At the same time, long-standing patterns of exclusion, subordination, and sectarian violence have resurfaced in recent developments.

Over the years, different minority communities in Syria have experienced violence, displacement, and recurring insecurity. Attacks on various groups, as well as repeated territorial and administrative shifts, have profound implications for local governance structures, deepening uncertainty among civilian populations. In this diverse and conflict-affected context, security concerns, territorial control, and acute political stabilization often become prioritized in decision-making processes, whereas social justice remains secondary. Social justice for minority communities in Syria, therefore, depends on political arrangements and strategic interests of national as well as international political actors.

One of these strategic interests concerns natural resources, as Syria’s northern area, predominantly Kurdish, is comparatively rich in them. This has turned the region into a space where different actors pursue their political and economic interests. Competition for territory and resources further complicates efforts to create inclusive governance structures and ensure equal access to opportunities. Especially minority communities often find themselves vulnerable in such environments, as their local realities become conditional on broader power dynamics. These contexts raise urgent questions regarding security guarantees, access to basic services, and sustainable livelihoods, especially for displaced populations, for whom such conditions are decisive when considering a possible return.

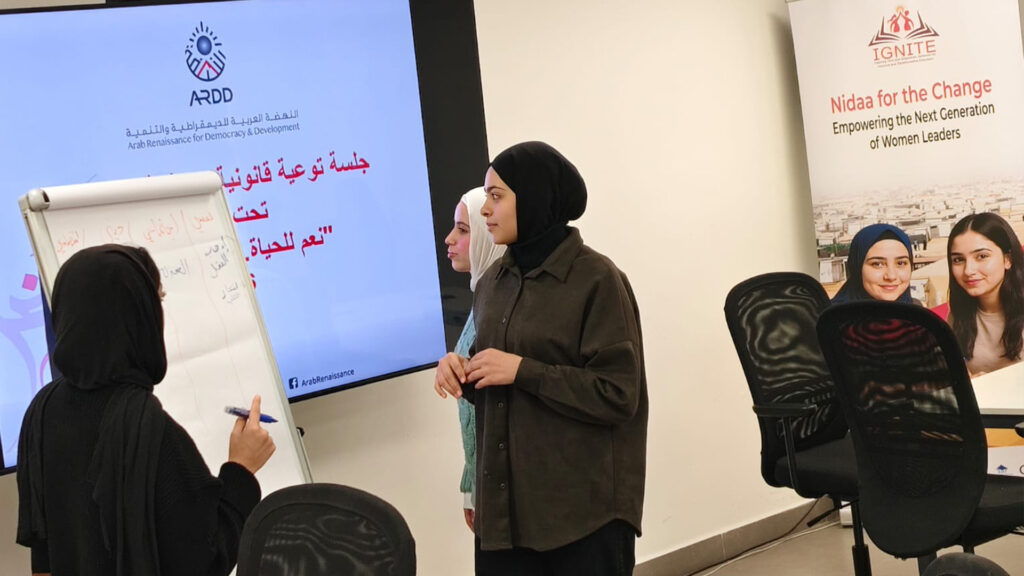

In such processes of reshaping governance structures, the political participation of affected minority groups can become marginalized. This has significant implications for social justice, since participation in political decision-making is not only a democratic principle but a prerequisite for social justice. Without real co-determination, rights remain precarious and contingent on shifting political interests. This dynamic demonstrates how prioritizing short-term stability in times of political crisis can reproduce patterns of exclusion and contribute to long-term injustice, making social justice secondary in contexts where it is urgently needed.

The case of Syria is not an isolated example, but reflects a broader regional pattern characterized by ongoing conflict and political exclusion. In many contexts across the Arab World, acute security concerns, territorial control, and short-term stability are prioritized, while questions of inclusive governance are postponed. This dynamic illustrates the tension between political priorities and social justice. Systems built on historical power asymmetries, unequal economic dependencies, political marginalization, and unfair access to resources and opportunities make achieving social justice increasingly difficult. When stability becomes the primary requirement for peace and development, and political participation is sidelined, it is necessary to critically ask for whom this stability is achieved — and whether it can be sustainable when efforts toward social justice are being left out.

The World Day of Social Justice thus highlights the enormous gap between global commitments and lived realities, especially in regions shaped by ongoing political crises. In such contexts, social justice cannot be postponed until political conditions improve or stability is fully attained – inclusive participation in decision-making processes, legal protection, and equitable governance must instead be recognized as integral components of any political process seeking lasting peace and stability. Otherwise, political arrangements that prioritize stability over inclusion risk institutionalizing social injustice rather than resolving it.